Picture this. You and your family all live in a small and very cramped one room home. There are spaces where there should be windows, but they are boarded-up and no light ever come through them.

Although you share the home with other members of your family, you find it really hard to see them, as the only illumination comes from a small, 5 watt bulb suspended from the middle of the room. So the room is very dimly lit and you can only ever catch glimpses of the other members of your family when they walk directly beneath the .light bulb.

Every-so-often water starts to drip down on to you and your family. This, you are told, is special water sent from God to bless you. Funny. But to you it feels cold and unpleasant. And not much of a blessing at all.

At regular intervals your family is visited by a pair of men who come to check on you and your family to ensure that all is well. They wear strange, thick clothing and have goggles on their faces to protect them from the evil that is outside of your hut.

They knock on the door with a special knock and are quickly hustled in, lest the evil influence of outside contaminate the home.

But still, you sometimes wonder what outside actually is and how evil it might really be. One evening, someone is a little slower than normal in closing the door and you catch a glimpse of outside. All you were able to see was that it looked really interesting. So, you decide to leave the safety of your family home to find out what outside was like.

When the others are praying with the visitors, you sneak out through the door, closing it behind you. You gaze around you. All you can do is say: Wow!” You see the remains of the setting sun in the West, watch the first stars coming out, twinkling in the gathering night.

You wander away, looking at everything. It all looks so beautiful. Presently, overcome by exhaustion, you fall asleep under a hedge.

The next morning you are awoken by the singing of many different types of birds. And you see the sun rise. You look around you, shielding your eyes. You are unaccustomed to such brightness, but your eyes gradually adjust.

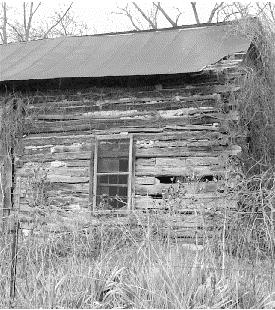

You retrace your footsteps as best you can. Eventually you find your home. What a terrible shock. Your home, of which your parents are so proud, is, you see, nothing but a small and cramped shack. But worse than that.

It is quite clear that it is built out of a variety of strange materials, all from different sources. Old packing crates, randomly sized bits of wood, all held together with bent nails, bits of old string. From where you stand you can see the flat roof of the hovel that you have called home all your life. There were so many holes in it that there was no wonder water fell on you and your family.

As you walk towards your home, you see a pair of the visitors staggering down the street, in their thick clothing, clutching each other. You wonder if one of them is ill. But then you notice that they are both wearing goggles that are totally painted over with black paint. They are clutching each other because they can barely see where they are going.

Somehow they make it to a neighbouring hovel that is similar to the one you call home. There are, you notice, a small number of these hovels all gathered together in a piece of rough land bounded by a tumbledown fence. There is a rickety slam as they are hustled into the hovel.

All around them there is fantastic beauty. Trees, vales, open pastures, farmland, gorgeous hills, valleys, majestic mountains. Everything. As your gaze shifts toward your home, the hovel, you start to weep. How could you and your family have lived in such a horrible home, whilst all around was not great evil and horrors but a truly beautiful world?

You resolve to tell your family the truth. You run to your door and open it. The action of your family surprises you. Shocks you, even. As the light of the day falls on them, they scream in terror. They push you out, shouting that you had been tainted by the evils of the world. They slam the door behind you, and you see the whole, pitiful shack shake and vibrate with the force.

You spend hours and hours hammering on the door, shouting for your family to join you in the light. But they do not even deign to give you a direct response. Instead they sing hymns to drown out the sound of your voice.

Eventually, you realise that you will never reach your family. So you turn to leave, noticing that it is already coming upon the evening time, again.

As you stand outside the hovel, wondering what to do next, several people approach you. They identify themselves as fellow former dwellers in the hovels with their own families. Some had their entire family with them, others one or two family members but most were like you, with only themselves having been able to escape their family’s hovel.

They invite you to join them. So you do, wandering off to see what great adventures might exist outside of the hovel that your family called home. Picture this.

4 comments:

You have captured exactly what it feels like so well in this great story!!! Can I copy a link to this post in a post on my blog? Please?!

wow, excellent story. Great construction; wonderfyl metaphores.

Very compelling and deep.

Very interesting approach!

Strangely enough, I have just recently read Plato's allegory of the cave, which is very poignant as well, but you capture an aspect in your allegory that Plato doesn't.

In Plato's cave, the people are not depicted as fearful of the outside world itself, but rather the stupefying effects of it on the returning prisoners, seemingly destroying their ability to understand the world within the cave. Because the allegory is silent as to what the other prisoners think about the world outside itself, they do not seem to fear what the returning prisoner will say, so much as they are hostile to any attempts to take any of their number outside. In other words, they do not seem to fear the actual knowledge of the outside, but simply find it to be unworthy of attention.

Plato obviously didn't live in a society dominated by reactionary salvation religions and propaganda. His allegory did not anticipate the coming war between rationalism and anti-rationalism -- that eventually those running the prison would not only work on more aggressive prisoner retention but would actively engender fear in both the ignorant prisoners and those who had been outside by demonizing the information itself.

Part of this is probably because Plato envisioned the allegory as applicable primarily to the untutored senses of man -- the prison is the individual himself, and the light is the intellectual world of understanding. In this sense, he sees the conflict as more directly between man's mind and senses, rather than between competing social groups or classes (for example, priests versus the tithers).

More pointedly, he was an elitist himself and had no interest, as you can read in his own commentary on the allegory, in bringing the majority of prisoners out. Indeed, contrary to his human-body interpretation of the cave, he expresses that the goal should be to expose select men to the light, teach them how to think, and send them back into the cave to rule as benevolent despots.

So he he interprets it himself on two different levels -- the body as the cave, and society as the cave. There is some direct and intended social commentary, but it is incomplete and not taken to its logical conclusion, perhaps because Greek civilization had not yet seen the sort of reaction against reason that makes this dynamic plainly-evident today. Even so, it seems to be a glaring omission, because he obviously sees foreshadowings of that hostility.

That logical conclusion is what you capture implicitly in your allegory: the reaction against the light itself by those who rule, supervise and lead the prisoners, and the irrational fear engendered among the prisoners themselves. The demonization of the world outside the confines of the belief system.

You capture well the fear that even slight exposure to the world outside of the belief system will contaminate the exposed people. In some ways, the imagery reminds me of one of those post-nuclear-holocaust movies, and I don't think that's a bad metaphor for how those within the belief system are taught to see the outside world.

Also, it's a very nice touch that you have the wanderer's family reject him and then, of all things, sing hymns to drown out his pleas.

Of course, different metaphors and allegories have different strengths. Plato's allegory may lack in the aspect I've discussed, but it is unsurpassed, perhaps, in describing the pain for the individual of seeing and accepting the outside world, giving up the comfortable and simple "truths" of the cave and seeing the deception for what it was. Yours does not focus on this aspect.

In the end, the tone of your piece comes off on the whole as a little more feel-good, perhaps to hearten people feeling alone and rejected after leaving a clannish, reactionary, and anti-rational belief-based community (Mormonism being the most obvious and intended such community), and to inform them that there are other such refugees outside in the ex-Mormon community. But that's not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, it may be very helpful given how gregarious Mormons are raised to be and how painfully alone one is left after being ostracized.

Just in case you find it interesting and haven't read it (it's in a LOT of basic college-level English anthologies), another great allegory that is very provocative in this context is The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, but I don't want to spoil it -- its power and beauty is in reading it as an experience, not anticipating what is to come.

Anyway, great writing! I look forward to reading more! And, as always, I apologize for the length of this comment.

Thank you for your detailed comment. And I am not bothered by how long it was.

Post a Comment